Life

We believe all human life is sacred and of inestimable worth in all its dimensions, including pre-born babies, the aged, those with disabilities, and every other stage or condition from fertilization to natural death.

- office@prolifems.org

- (601) 956-8636

- P.O. Box 320042, Flowood, MS 39232

Disabilities

Disability is a physical or mental impairment that substantially limits one or more of a person’s major life activities. It can be present at birth or come about in a moment of crisis, such as an accident or injury, or it can emerge over time, such as a visual impairemtn or multiple sclerosis. It may be short term or long term, and it may include physicla or intellectual impairments or both.

While each individual with disabilities faces unique challenges, they all have one thing in common: THEY ARE PEOPLE FIRST. They experience the same joy, fear, sadness, and love as everyone else.

They want to be valued members of the community and to participate in life to the best of their abilities. And they all have a great deal to teach about the important things in life.

History

Infanticide has a long history, and several cultures have routinely practiced it for several reasons including birth control, destroying handicapped individuals seen as unfit, and to kill female children because of the cultural preference for males. While infanticide is currently considered a much bigger taboo than abortion in America, it still takes place today in the U.S. and in other countries around the world.

According to The Society for the Prevention of Infanticide In 1978, Laila Williamson, an anthropologist of the American Museum of Natural History, summarized the data she had collected on the prevalence of infanticide among tribal and civilized societies from a variety of sources in the scientific and historical literature. Her conclusion was startlingly blunt:

Infanticide has been practiced on every continent and by people on every level of cultural complexity, from hunters and gatherers to high civilization, including our own ancestors. Rather than being an exception, then, it has been the rule.

Most societies agree that the drive to protect and nurture one’s infant is a basic human trait. Yet infanticide—the killing of an infant at the hands of a parent—has been an accepted practice for disposing of unwanted or deformed children since prehistoric times. Despite human repugnance for the act, most societies, both ancient and contemporary, have practiced infanticide. Based upon both historical and contemporary data as many as 10 to 15 percent of all babies were killed by their parents.

Born-Alive Protection

Not long ago, the issue of infanticide was unknown to many in the United States, but recently several states across the country have been legalizing infanticide. These states enacted legislation that included removing all protections of babies born alive after failed abortions. How is this possible?

The majority of Americans are in favor of Born-Alive protections and think late-term abortions are wrong.

The Born-Alive Infants Protection Act of 2002 (“BAIPA”, enacted August 5, 2002) amended the definitions section of Title 1, Chapter 1 of United States Code, Section 8. As an Act of Congress, it extends legal protection to an infant born alive after a failed attempt at induced abortion. It passed unanimously in the Senate. It was signed by President George W. Bush.

July 2019 – U.S. Department of Health and Human Services agency re-issued a memo to all hospitals detailing requirements under the law (specifically EMTALA and the BAIPA) for emergency medical assessments and stabilization efforts to any person, including infants born alive after failed abortions. Reporting violations of EMTALA is the responsibility of individuals, including hospital staff or a layperson.

Susan B Anthony’s list organization has a livestream video link of the hearing on the Born alive Survivors Protection Act.

Trends

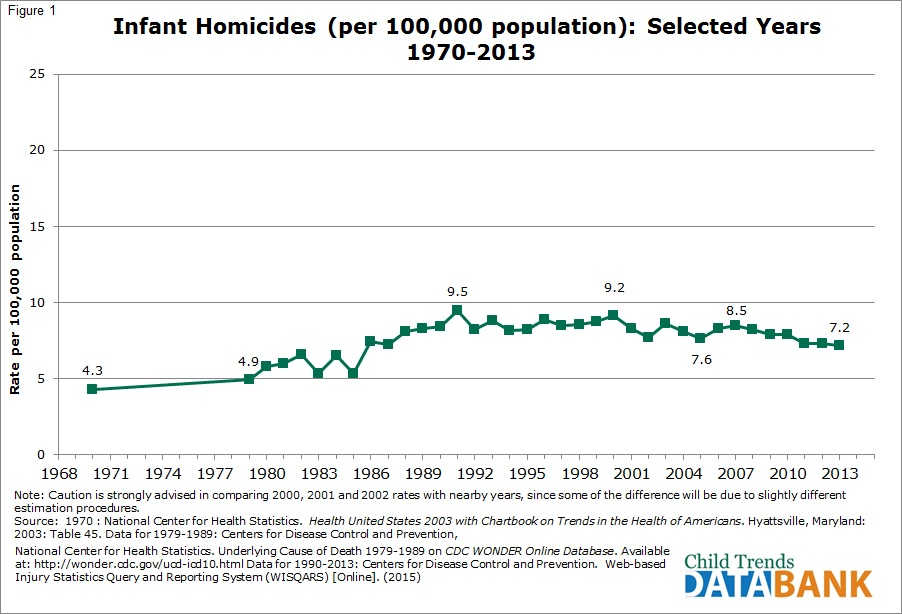

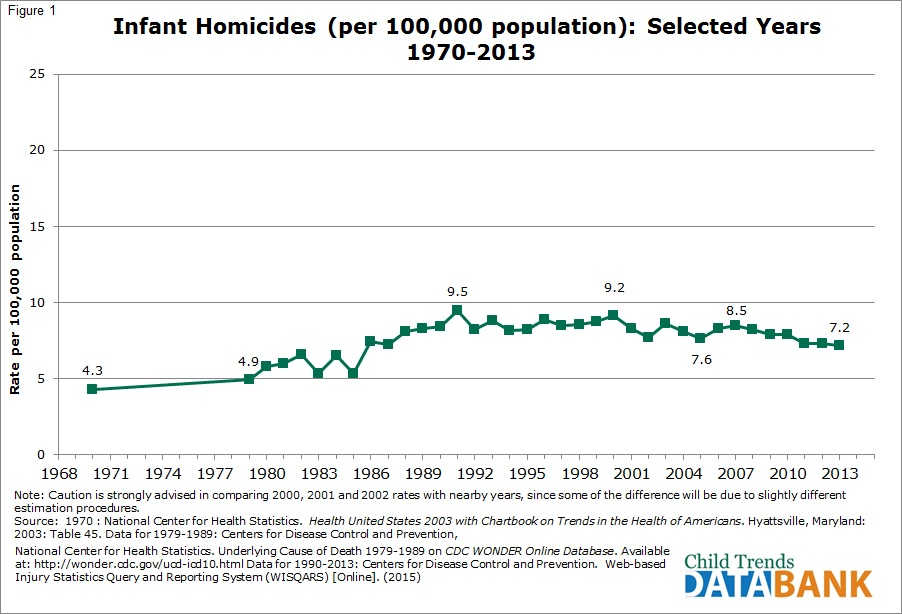

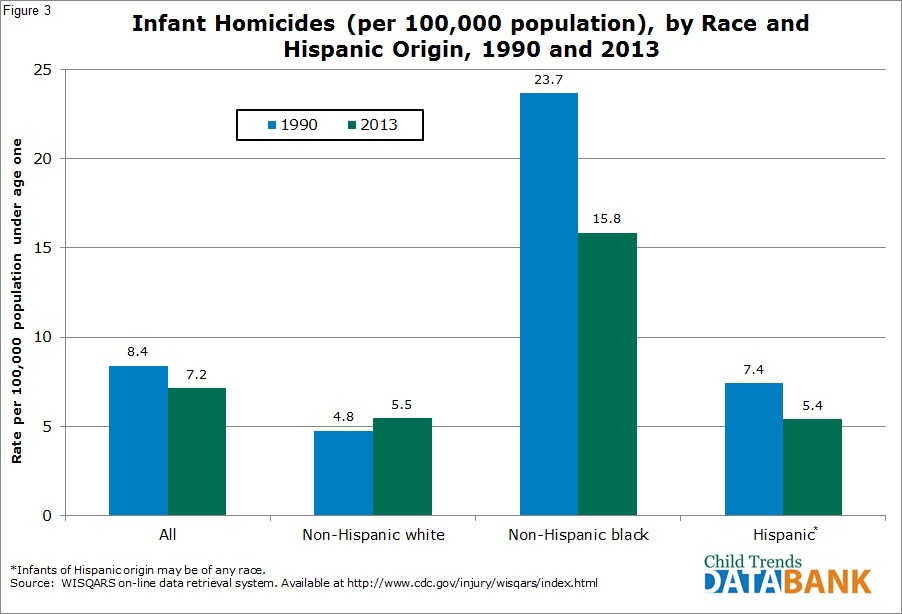

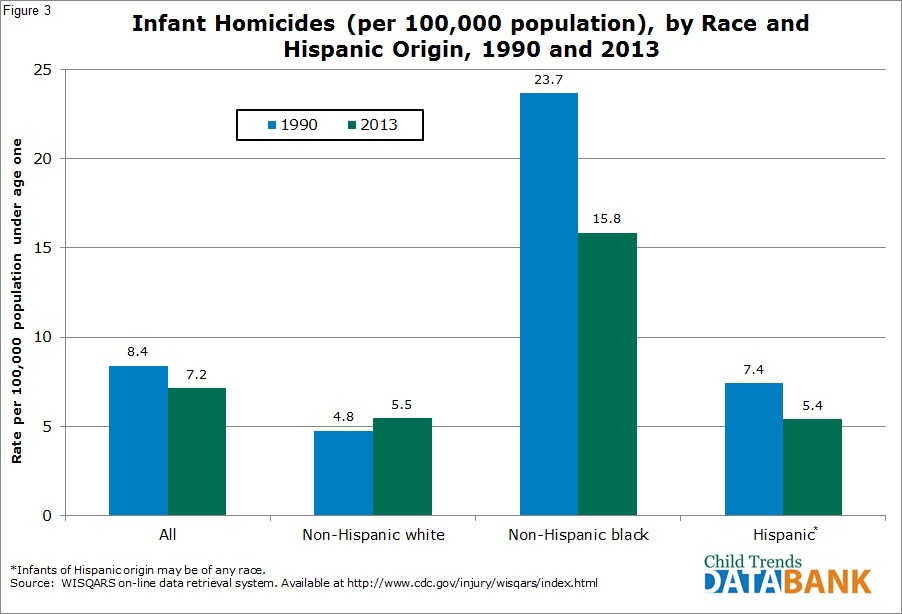

Between 1970 and 1991, the infant homicide rate more than doubled, from 4.3 to 9.5 infant deaths per 100,000 children under age one. The rate was fairly stable between 1991 and 2000, but the trend has been generally downward since then, and was at 7.2 deaths per 100,000 in 2013.

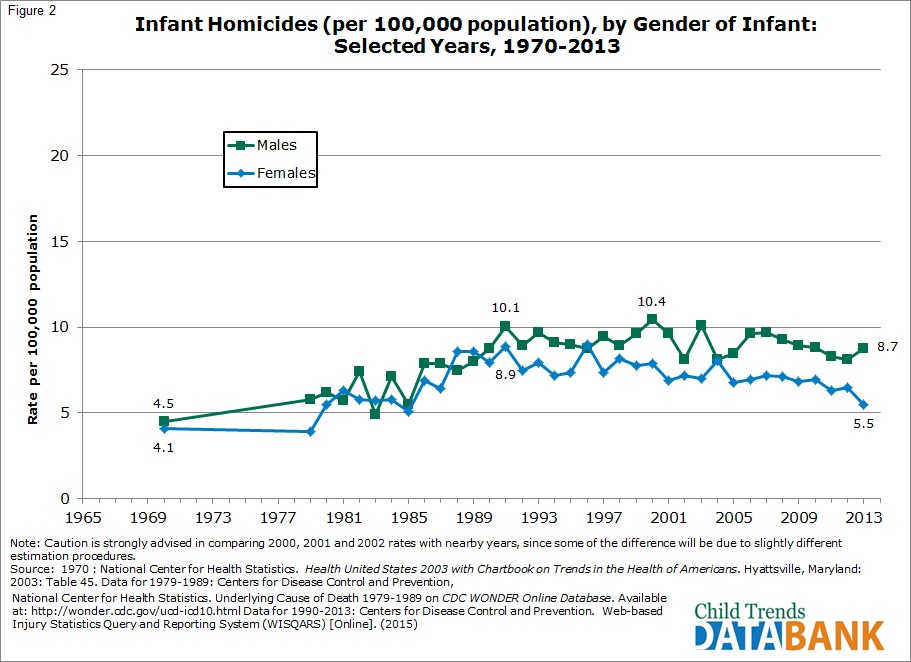

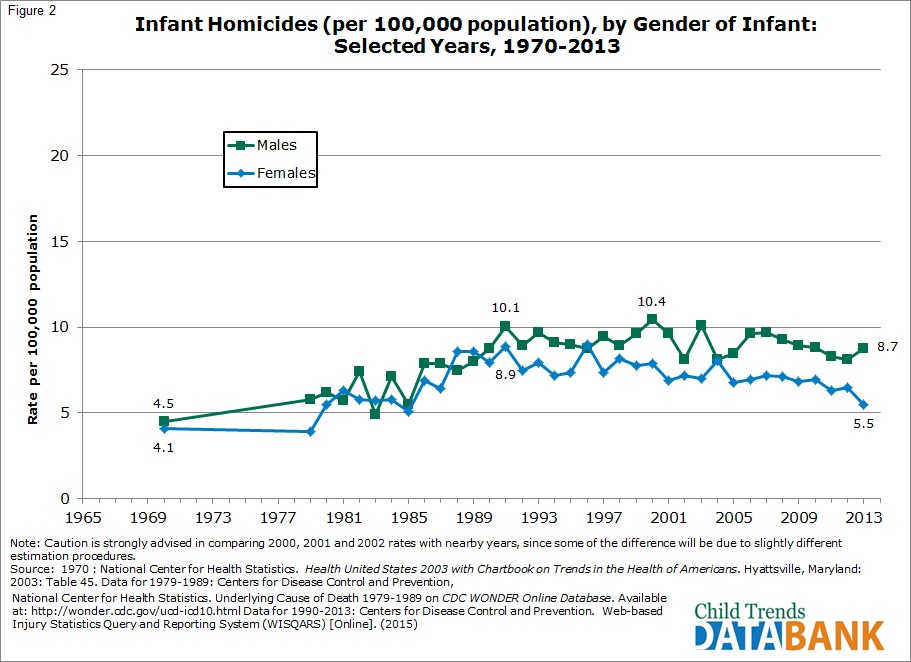

In most years, males have been more likely than females to be killed during the first year of life. In 2013, for example, the infant homicide rate for boys was 8.7 per 100,000 children under age one and 5.5 for girls. This gap has generally widened since 1970.

Black infants are substantially more at risk for homicide than are other infants. In 2013, the homicide rate for black infants was 15.8 per 100,000, while Hispanic and white infants had rates of 5.5 and 5.4 per 100,000, respectively. However, the rate for black infants has decreased greatly since 1990, when it was at 23.7 per 100,000.

Euthanasia & Assisted Suicide

Medical Definition of Euthanasia

The act or practice of causing or permitting the death of hopelessly sick or injured individuals (such as persons or domestic animals) in a relatively painless way for reasons of mercy—called also mercy killing.

Legal Definition of Euthanasia

The act or practice of killing or permitting the death of hopelessly sick or injured persons in a relatively painless way for reasons of mercy —called also mercy killing.

In the majority of countries euthanasia or assisted suicide is against the law. According to the National Health Service (NHS), UK, it is illegal to help somebody kill themselves, regardless of circumstances. Assisted suicide, or voluntary euthanasia carries a maximum sentence of 14 years in prison in the UK. In the USA the law varies in some states.

There are two main classifications of euthanasia:

Voluntary euthanasia

this is euthanasia conducted with consent. Since 2009 voluntary euthanasia has been legal in Belgium, Luxembourg, The Netherlands, and Switzerland. 5 states (CA, CO, OR, VT, and WA) and DC legalized physician-assisted suicide via legislation. 1 state (MT) has legal physician-assisted suicide via court ruling.

Involuntary euthanasia

euthanasia is conducted without consent. The decision is made by another person because the patient is incapable of doing so himself/herself.

There are two procedural classifications of euthanasia:

Passive euthanasia

this is when life-sustaining treatments are withheld. The definition of passive euthanasia is often not clear-cut. For example, if a doctor prescribes increasing doses of opioid analgesia (strong painkilling medications) which may eventually be toxic for the patient, some may argue whether passive euthanasia is taking place – in most cases, the doctor’s measure is seen as a passive one. Many claim that the term is wrong because euthanasia has not taken place, because there is no intention to take life.

Active euthanasia

lethal substances or forces are used to end the patient’s life. Active euthanasia includes life-ending actions conducted by the patient or somebody else.

USA Euthanasia Laws

New York 1828 An anti-euthanasia law was passed in the state of New York in 1828. It is the first known anti-euthanasia law in the USA. In subsequent years many other localities and states followed suit with similar laws. Several advocates, including doctors, promoted euthanasia after the American Civil War. At the beginning of the 1900s support for euthanasia peaked in the USA, and then rose up again during the 1930s.

A turning point in the euthanasia debate occurred after a public outcry over the Karen Ann Quinlan (1954-1985) case.

Derek Humphry (born 1930), a British-born American journalist founded the Hemlock Society in Santa Monica, California. At the time it was the only group in the USA to provide information to terminally ill patients in case they wished to hasten death. The society also campaigned and contributed financially to drive to amend legislation. In 2003 Hemlock merged with End of Life Choices, changing their name to Compassion and Choices.

In 1990 the Supreme Court approved the use of non-active euthanasia.

Dr. Jack Kevorkian (1928), an American pathologist, right-to-die activist, painter, composer, and instrumentalist, was tried and convicted in 1992 for a murder displayed on the TV. He had already become infamous for encouraging and assisting people in committing suicide. He claimed to have assisted at least 130 patients to that end. He famously said that “dying is not a crime.”

Oregon 1994 – Oregon voters approved the Death with Dignity Act in 1994, allowing physicians to assist terminal patients who were not expected to survive more than six months. The US Supreme Court adopted such laws in 1997. In 2001 the Bush administration tried unsuccessfully to use drug law to stop Oregon in 2001, in the case Gonzales v. Oregon. Texas introduced non-active euthanasia legally in 1999.

Terri Schiavo case – a seven-year long legal case which dealt with whether Terri Schiavo, a patient diagnosed as being in a persistent vegetative state for many years, could be disconnected from life support. In 1993, Michael Schiavo, her husband and guardian, asked the nursing home staff not to resuscitate her – however, the staff convinced him to withdraw the order.

In 1998, Michael petitioned the Sixth Circuit Court of Florida to remove her feeding tube under Florida Statutes Section 765.401(3). However, Robert and Mary Schindler (Terri’s parents) argued that she was conscious and opposed the petition. Michael eventually transferred his authority over the issue to the court. The court concluded that the patient would not wish to continue life-prolonging measures.

Terri Schiavo’s feeding tube was withdrawn on April 24, 2001, and reinserted some days later as legal decisions were made. This attracted the attention of the media, and subsequently that of politicians and advocacy groups, especially pro-life and disability rights groups.

Members of the Florida Legislature, the US Congress and even the President of the USA started talking about it. President Bush returned to Washington D.C from a vacation in March 2005 to sign legislation aimed at keeping Schiavo alive. This move turned the case into a national topic for most of the month.

The Schiavo case involved 14 appeals, several motions, petitions and hearings in the Florida courts, five suits in federal district court, Florida legislation was struck down by the Supreme Court of Florida, a subpoena by a congressional committee to qualify Schiavo for witness protection, and some other legal proceedings. Eventually the local court’s decision to disconnect Schiavo from life support was acted upon on March 18th, 2005 – Schiavo died on March 31st.

Washington state – the Washington Initiative 1000 made Washington the 2nd state in the USA to legalize doctor-assisted suicide.

37 states have laws prohibiting assisted suicide. 3 states (AL, MA, and WV) prohibit assisted suicide by common law. 4 states (NV, NC, UT, and WY) have no specific laws regarding assisted suicide, may not recognize common law, or are otherwise unclear on the legality of assisted suicide.

The federal government and all 50 states prohibit euthanasia under general homicide laws. The federal government does not have assisted suicide laws. Those laws are generally handled at the state level.

“The history of the law’s treatment of assisted suicide in this country has been and continues to be one of the rejection of nearly all efforts to permit it. That being the case, our decisions lead us to conclude that the asserted ‘right’ to assistance in committing suicide is not a fundamental liberty interest protected by the Due Process Clause.”

“Activists often claim that laws against euthanasia and assisted suicide are government mandated suffering. But this claim would be similar to saying that laws against selling contaminated food are government mandated starvation.

Laws against euthanasia and assisted suicide are in place to prevent abuse and to protect people from unscrupulous doctors and others. They are not, and never have been, intended to make anyone suffer.”

“In a society as obsessed with the costs of health care and the principle of utility, the dangers of the slippery slope… are far from fantasy…

Assisted suicide is a halfway house, a stop on the way to other forms of direct euthanasia, for example, for incompetent patients by advance directive or suicide in the elderly. So, too, is voluntary euthanasia a halfway house to involuntary and nonvoluntary euthanasia. If terminating life is a benefit, the reasoning goes, why should euthanasia be limited only to those who can give consent? Why need we ask for consent?”

“The False Promise of Beneficent Killing,” Regulating How We Die: The Ethical, Medical, and Legal Issues Surrounding Physician-Assisted Suicide 1998

“The prohibition against killing patients… stands as the first promise of self-restraint sworn to in the Hippocratic Oath, as medicine’s primary taboo: ‘I will neither give a deadly drug to anybody if asked for it nor will I make a suggestion to this effect’… In forswearing the giving of poison when asked for it, the Hippocratic physician rejects the view that the patient’s choice for death can make killing him right. For the physician, at least, human life in living bodies commands respect and reverence–by its very nature. As its respectability does not depend upon human agreement or patient consent, revocation of one’s consent to live does not deprive one’s living body of respectability. The deepest ethical principle restraining the physician’s power is not the autonomy or freedom of the patient; neither is it his own compassion or good intention. Rather, it is the dignity and mysterious power of human life itself, and therefore, also what the Oath calls the purity and holiness of life and art to which he has sworn devotion.”

“Neither for Love nor Money,” Public Interest Winter 1989

“Cases like Schiavo’s touch on basic constitutional rights, such as the right to live and the right to due process, and consequently there could very well be a legitimate role for the federal government to play. There’s a precedent–as a result of the highly publicized deaths of infants with disabilities in the 1980s, the federal government enacted ‘Baby Doe Legislation,’ which would withhold federal funds from hospitals that withhold lifesaving treatment from newborns based on the expectation of disability. The medical community has to have restrictions on what it may do to people with disabilities – we’ve already seen what some members of that community are willing to do when no restrictions are in place.”

“End of Life Planning: Q & A with Disabilities Advocate,” Reno Gazette-Journal Nov. 22, 2003

“Studies show that hospice-style palliative care ‘is virtually unknown in the Netherlands [where euthanasia is legal].’ There are very few hospice facilities, very little in the way of organized hospice activity, and few specialists in palliative care, although some efforts are now under way to try and jump-start the hospice movement in that country…The widespread availability of euthanasia in the Netherlands may be another reason for the stunted growth of the Dutch hospice movement. As one Dutch doctor is reported to have said, ‘Why should I worry about palliation when I have euthanasia?’”

“Savings to governments could become a consideration. Drugs for assisted suicide cost about $35 to $45, making them far less expensive than providing medical care. This could fill the void from cutbacks for treatment and care with the ‘treatment’ of death.”

“It must be recognized that assisted suicide and euthanasia will be practiced through the prism of social inequality and prejudice that characterizes the delivery of services in all segments of society, including health care. Those who will be most vulnerable to abuse, error, or indifference are the poor, minorities, and those who are least educated and least empowered. This risk does not reflect a judgment that physicians are more prejudiced or influenced by race and class than the rest of society – only that they are not exempt from the prejudices manifest in other areas of our collective life.

While our society aspires to eradicate discrimination and the most punishing effects of poverty in employment practices, housing, education, and law enforcement, we consistently fall short of our goals. The costs of this failure with assisted suicide and euthanasia would be extreme. Nor is there any reason to believe that the practices, whatever safeguards are erected, will be unaffected by the broader social and medical context in which they will be operating. This assumption is naive and unsupportable.”

“As Catholic leaders and moral teachers, we believe that life is the most basic gift of a loving God- a gift over which we have stewardship but not absolute dominion. Our tradition, declaring a moral obligation to care for our own life and health and to seek such care from others, recognizes that we are not morally obligated to use all available medical procedures in every set of circumstances. But that tradition clearly and strongly affirms that as a responsible steward of life one must never directly intend to cause one’s own death, or the death of an innocent victim, by action or omission…

We call on Catholics, and on all persons of good will, to reject proposals to legalize euthanasia.”

“Not only are we awash in evidence that the prerequisites for a successful living wills policy are unachievable, but there is direct evidence that a living will regularly fails to have their intended effect…

When we reviewed the five conditions for a successful program of living wills, we encountered evidence that not one condition has been achieved or, we think, can be. First, despite the millions of dollars lavished on propaganda, most people do not have living wills… Second, people who sign living wills have generally not thought through its instructions in a way we should want for life-and-death decisions… Third, drafters of living wills have failed to offer people the means to articulate their preferences accurately… Fourth, living wills too often do not reach the people actually making decisions for incompetent patients… Fifth, living wills seem not to increase the accuracy with which surrogates identify patients’ preferences.”

Angela Fagerlin, PhD Core Faculty Member, Robert Wood Johnson Clinical Scholar Program, University of Michigan Medical School Carl E. Schneider, JD Chauncey Stillman Professor for Ethics, Morality, and the Practice of Law, University of Michigan Law School “Enough: The Failure of the Living Will,” Hastings Center Report 2004